I’ve been reading Range by David Epstein. It’s about how some of the world’s greatest talents didn’t specialise early, but instead dabbled about before eventually finding their thing.

Take Tiger Woods: golf club in hand practically from birth, the poster child of early specialisation. And then Roger Federer: the lad who tried everything – football, skiing, basketball, badminton, probably competitive hopscotch – before he finally picked up a tennis racket properly in his teens. And guess what? He still ended up being Roger fucking Federer.

And then there’s the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice. Back in Renaissance Italy, this was an orphanage for abandoned girls – but it wasn’t just a home. It became one of Europe’s most prestigious music schools. The girls trained under masters like Antonio Vivaldi, and here’s the key bit: they didn’t just play one instrument. They were trained on multiple instruments, often to a ridiculously high standard. A girl might be singing one week, leading the violin section the next, and filling in on the oboe the week after. Specialism? Forget it. Their brilliance came from being versatile, flexible, and able to turn their hands (and lips, and bows) to whatever was needed.

The result? Their concerts became legendary. Audiences of aristocrats and tourists queued up to hear them, not just because the music was beautiful, but because these were orphans, abandoned by society, who had been trained into some of the finest musicians in Europe. A dabbling triumph if ever there was one. Meanwhile, back in my classroom, I’m just trying to get Year 9 to all play in the same key at the same time without turning “Three Little Birds” into a death metal anthem.

Epstein’s point is this: dabbling is good. It’s not a weakness, it’s the making of people. Greatness can come from the kid who doesn’t fit the neat “one path from day one” model. Sometimes the late bloomers and the wide experimenters end up overtaking the prodigies.

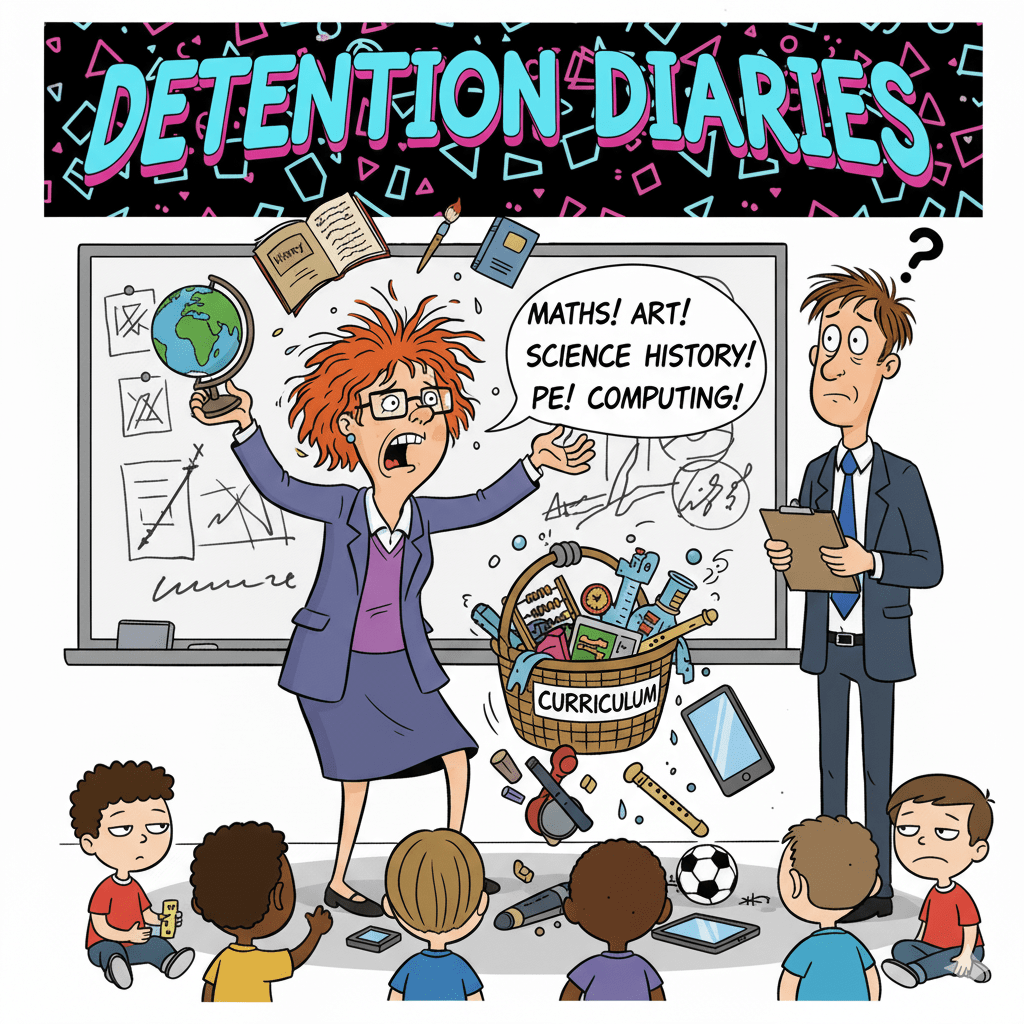

Which brings me to Ofsted and their favourite phrase: the “broad and balanced curriculum.” You know, that line that inspectors drop into reports like confetti. Broad and balanced. Lovely words. Sounds like the name of an upmarket café that sells overpriced sourdough.

But here’s the question: has anything actually changed? We’re told the curriculum is “at the heart of everything.” But in reality, most of us are still wrestling with exam specs, cramming in enrichment, dodging the latest acronym, and making sure Kyle hasn’t set fire to the glue sticks again.

Broad and balanced, in practice, often means: “Make sure your PowerPoint has intent, implementation, impact plastered across it and you’ll be fine.” As if a child discovering their hidden talent in, say, ceramics, is just a by-product of an inspection framework rather than, you know, the actual point.

If Federer had been through the English system, he’d have been forced into “tennis interventions” from Year 7, tracked as “working towards” on SIMS, and probably had his parents called in because he kept bunking off rounders. Tiger Woods would have had an EHCP for “exceptional golf needs” by the age of five. And the Ospedale della Pietà? Shut down immediately for non-compliance with health and safety, lack of differentiated worksheets, and an insufficiently detailed SEF.

The truth is, kids need range. They need the freedom to dabble, to fail, to try a clarinet one week and handball the next. To muck about a bit, and through that, stumble on the thing that might just change their life. That is what “broad and balanced” should mean. Not three bullet points on a PowerPoint slide, but giving kids a shot at finding their Federer moment.

So maybe Epstein’s right. Maybe dabbling isn’t dangerous – maybe it’s essential. And maybe, just maybe, next time an inspector comes into my classroom, I’ll explain that. Right after I’ve confiscated a drumstick from Kyle and stopped Year 8 playing the Jet 2 holidays song for the fiftieth time this week.

Leave a comment