Really slowly… then all at once!

Every few months something happens that makes you think. Something that opens your eyes to something you perhaps knew was there but didn’t really pay attention to. Perhaps there was a little wet patch above the lounge “It’ll be alright, we’re coming up to winter, perhaps its just condensation”. Maybe there is a slow puncture on your tyre, you keep filling your tyres with air and you know you’ve got to change it eventually “I’ll get it sorted next week.”.

Then comes a report that opens your eyes and you realise the problem is far worse than you thought. That wet patch above the lounge is in fact a leaky pipe and the first floor has flooded without you knowing. That slow puncture is in fact something wrong with the suspension and you need to get some serious work done on your car.

The NASUWT’s Where Has All the Money Gone? is one of those.

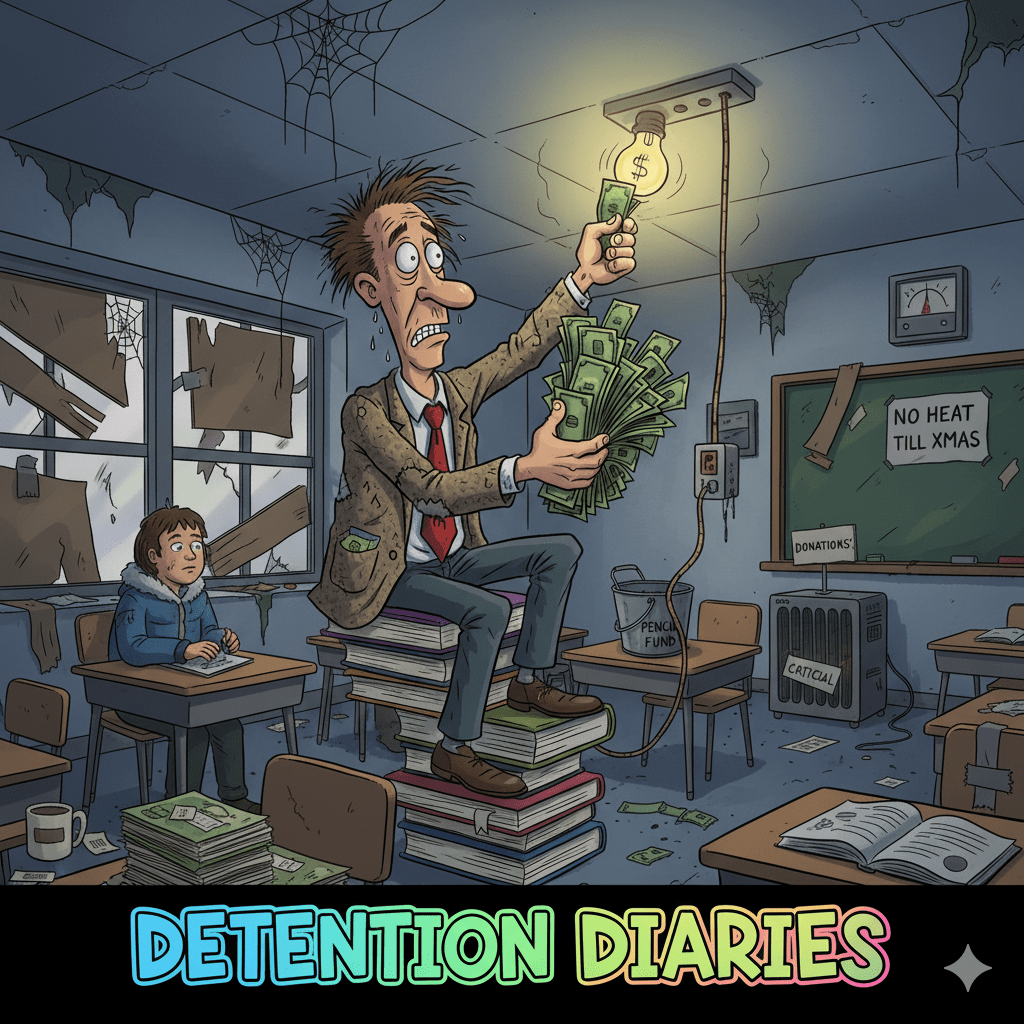

A report that confirms what we already feel every single day: schools are struggling, not because teachers don’t care or try hard enough, but because money is being swallowed up by a system that’s become more about management, middlemen, and marketing than about children and learning.

The report highlights billions being drained from frontline education — and as someone living both in education and alongside it as a parent of a child with additional needs, I can tell you firsthand: it shows.

The Reality Behind SEND Spending

The report’s section on SEND hit me hardest. It says private providers are charging as much as £61,500 per child per year — that’s nearly triple what state provision costs.

On paper, you’d expect that kind of money to mean gold-standard support, specialist help, and truly tailored provision.

In reality, it often doesn’t.

As a parent trying to get help for my autistic daughter, I’ve seen how exhausting and confusing the system is.

You’d think that once you have a diagnosis, the help would slot into place — support in school, professionals who understand, adaptive teaching, and genuine conversations about how she can thrive, not just survive.

But it’s not like that at all. It’s forms, assessments, waiting lists, emails to nobody, and more forms. You end up fighting the system that’s supposed to be fighting for your child.

So when I read that billions are being spent on SEND services and support contracts, I have to ask — where’s the impact? Where’s the human bit?

Because for all the talk of inclusion and “quality first teaching,” what I see is overstretched teachers doing their absolute best without the resources or training they need, and children slipping through the cracks while money slips out of the system.

The Business of Education

Education is no longer a sector — it’s an industry.

We’ve got Multi-Academy Trusts (MATs), private consultants, management firms, data contractors, HR services, outsourced payroll, behaviour intervention teams, agency teachers, and “school improvement” companies — all making tidy sums from public money that used to go directly into schools.

There’s a whole ecosystem built around education, and everyone’s feeding from it except the people actually in the classroom.

It’s fragmented, messy, and full of duplication. One MAT might be paying one company for “strategic leadership training,” while another pays for the same thing rebranded with a new logo.

Meanwhile, actual teachers are told to reuse exercise books and print double-sided to save paper.

When did education stop being about the children and start being about the contracts?

The Cost of Keeping the Lights On

Then there’s the issue of cover.

Schools are now spending millions just to have a body in the room. Not necessarily a qualified teacher — just someone to keep the peace, supervise a worksheet, and make sure nobody throws a chair.

The NASUWT report says schools spent around £1.2 billion on supply teachers last year, with £300 million going straight to agencies.

That’s £300 million that could have been used for proper teacher recruitment, training, or retention — you know, the things that actually stop people from leaving in the first place.

We’ve reached a point where we’re paying to prop up the symptoms of a broken system rather than fixing the causes of it.

Too Many Chiefs, Not Enough Teachers

Some MATs now have four layers of management above the headteacher.

Four.

You’ve got the CEO, the deputy CEO, the regional director, the executive principal, the cluster lead, the area improvement strategist (whatever that means), and then, finally, the person who actually runs the school.

Some of these executives are earning over £250,000 a year. A few, apparently, are on more than £500,000.

Let that sink in.

The Prime Minister earns around £170,000.

So yes — we now live in a country where the leader of a group of schools can earn significantly more than the leader of the country.

And I’m sure they’ll say it’s because of the “scale of responsibility” or the “complexity of leadership.” But if the system they’re leading is underfunded, short-staffed, and leaking money, how complex can it be?

It feels less like a network of schools and more like a corporate pyramid scheme with a safeguarding policy.

Sometimes I wonder what would happen if we stopped paying for extra layers of management and instead paid for time. Time for teachers to plan properly, to talk to students, to actually collaborate. Time for SEND teams to work with parents, not just around them.

The money’s there — it’s just being vacuumed upwards instead of poured where it matters.

And honestly, at this point, I wouldn’t be surprised if the next report revealed that a MAT CEO is earning loyalty points on the government’s moral credit card.

Because when a system meant to nurture children becomes one that rewards profit and PowerPoint slides, it’s clear that the crisis isn’t in teaching — it’s in leadership.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to email my local authority again about my daughter’s support plan.

I expect a reply around 2043.

Leave a comment